Table of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Introduction

- The Population of Older Californians Will Continue to Grow and Diversify

- Older Californians’ Economic Circumstances Vary

- Living Arrangements and Well-being Are Key Concerns

- Policy Implications and Next Steps

- Notes and References

- Authors and Acknowledgments

- PPIC Board of Directors

- Copyright

Key Takeaways

California is on the cusp of an unprecedented demographic shift, with projections indicating a dramatic increase in the older adult population by 2040. This report examines and projects characteristics of the state’s older population and offers policy insights to help state leaders and stakeholders plan for this demographic shift.

- Dramatic growth. By 2040, 22 percent of Californians will be 65 or older, up from 14 percent in 2020. The older population (aged 65+) will increase by 59 percent, while the working-age population (aged 20–64) will remain largely unchanged and the child population (aged 0–17) will decrease by 24 percent. This shift will result in an old-age dependency ratio of 38 older adults per 100 working-age adults, up from 24 in 2020, and the highest ever recorded. →

- Culturally and linguistically competent care. The older adult population will become increasingly diverse, with no single racial or ethnic group constituting a majority. Growth rates will be highest among Latino and Asian older adults. A high proportion of Latino (60%) and Asian (85%) older adults will be foreign born, with about 75 percent speaking a language other than English at home. This increasing diversity will require culturally and linguistically appropriate services and a more diverse health care workforce. →

- Support for older homeowners and renters. Seven in ten older adults are projected to be homeowners by 2040, slightly down from 73 percent in 2020. Some will be “housing rich, income poor.” The 27 percent who will be renters face greater financial burdens due to lower incomes and increasing housing costs. →

- Workplace adaptations to support older workers remaining in the labor force. The share of older adults with incomes less than twice the federal poverty level is expected to decline but remain substantial at 22 percent in 2040 (down from 24% in 2000)—and given the large increases in the number of older adults, there will be about 600,000 more who are low-income in 2040. Labor force participation is projected to increase for those aged 65 to 74, especially among less-educated workers, possibly out of financial necessity. →

- Expanded resources for family caregivers. Family connections will remain crucial, with 59 percent of older adults living with a spouse and the share living alone decreasing from 22 percent to 18 percent. However, challenges in independent living will persist. Among adults over 80, one in three will have difficulties staying in their homes without assistance, and one in five will experience self-care limitations. →

- Meeting increased demand for Medi-Cal and home and community-based services. Despite a 51 percent increase in older adults in institutional settings, only 3 percent of the total older population is expected to live in such facilities. The vast majority are expected to remain in their own homes. →

Introduction

California is entering an unprecedented demographic era, with declining populations of working-age adults and rapid growth in the number of older adults. These changes will have large impacts on the state, including:

- Fewer workers as more Californians retire

- Higher demand for health care services and the workers who provide those services

- Greater need for long-term care

- Budgetary challenges stemming from fewer income tax payers and more older adults requiring services

To help them prepare for this major demographic challenge, state policymakers have put together a Master Plan on Aging (MPA) that provides a roadmap to support the health and well-being of Californians ages 60 and over. Launched in 2021, the MPA focuses on five key goals: housing, health, inclusion/equity, caregiving, and economic security for older adults and people with disabilities. Central to the MPA is the use of data to drive decision-making and track progress. A Data Dashboard for Aging monitors key indicators (such as poverty status, education, and homelessness), while an Implementation Tracker provides updates on specific initiatives. These tools are meant to help guide policy and funding decisions as California works towards creating an age- and disability-friendly state. However, many of these measures lack current data; data on future changes in socioeconomic and other characteristics of the state’s older population is limited.

In this report, we aim to inform the policymaking process by examining how California’s older population is projected to change. We also highlight characteristics of the older population that are most relevant to policy and program considerations (Department of Finance 2024), including:

Care needs for the oldest Californians. Californians who are 85 years old and over have substantially greater health care needs and levels of disability. Managing and financing their care will require careful planning as this demographic grows in size.

Rising demand for Medi-Cal and other care services. Medi-Cal is already the primary payer for long-term care and is taking on increasing importance in home- and community-based services that help Californians age in place. Given the projected increase in the number of low-income older adults, it will be crucial to prepare the Medi-Cal program to respond effectively. The In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program will also experience substantial growth, necessitating increased resources and potentially expanded eligibility criteria.

Labor force participation. Working will help some older adults cover their cost of living, especially those with few financial resources, but workplace adaptations will be needed for older workers.

Race/ethnicity and nativity. California’s increasingly diverse older adult population will have a range of cultural and linguistic needs and preferences for health care, multigenerational living arrangements, and aging services.

Housing stability. Helping homeowners modify their homes to age in place, and helping older renters stay housed, will keep older Californians in their communities and reduce unnecessary transitions to nursing care.

Difficulty with self-care and/or independent living. Understanding the extent to which older adults have assistance and companionship, especially if they have difficulties meeting all of their own needs, is helpful for planning Medi-Cal investments in home- and community-based services and can provide information about family caregiving.

In the bulk of the report, we highlight Department of Finance and our own projections of key characteristics of the state’s older population. We then discuss some implications of our findings and highlight future avenues for research.

The Population of Older Californians Will Continue to Grow and Diversify

The significant shifts in California’s demographic landscape over the past two decades are projected to continue and even accelerate through 2040. Several key factors are driving these changes: the aging of the baby boom generation, increased longevity, and the long-term effects of past immigration patterns.

The baby boom, from 1946 to 1964, created exceptionally large population cohorts that are now entering older ages. The youngest baby boomers are now 60 years old while the oldest are 78; in 2040 the youngest will be 76 and the oldest will be 94. As this generation ages, the older adult population is increasing significantly. Because of advances in health care and improved living conditions, people are living longer, but they are also living through more disabled years (Tesch-Römer and Wahl 2016).

It is important to note that the COVID-19 pandemic caused a brief (and traumatic) deviation from the long-term pattern of increases in life expectancy. The latest estimates suggest that life expectancy has resumed its pre-pandemic trend of gradually increasing longevity. The Department of Finance projects moderate increases in life expectancies through 2060.

California’s Older Adult Population Will Increase Dramatically

By 2040, California’s older adult population (aged 65 and over) is projected to increase by a remarkable 59 percent, from 5.7 million to just over 9 million. This growth stands in stark contrast to the projected changes in other age groups. The working-age population (20–64 years old) is expected to increase only 3 percent, while the population under age 20 is anticipated to decrease by 23 percent. California is projected to have 3.4 million more older adults aged 65 and over, and 1.7 million fewer residents less than 65 years old.

This disproportionate growth in the older population will lead to a significant shift in the state’s age structure. Almost one-quarter of Californians (22%) will be age 65 or older by 2040, a substantial increase from 14 percent in 2020. The old-age dependency ratio (the number of older adults per 100 adults of working ages) is projected to grow from 24 to 38. In other words, there will be 38 older adults for every 100 working adults in the state.

The most dramatic growth is projected among the oldest age groups—or the oldest old (Figure 1). The population aged 80 and over is expected to more than double, increasing by nearly 1.8 million in 2040. This rapid growth in the oldest age groups, driven by both the aging of the baby boomers and increases in longevity, is especially significant because of this group’s relatively high personal care and health care needs. The dramatic population increase for this group overwhelms any improvements in well-being. For example, there will be so many more very old Californians that reductions in the share with self-care limitations will not counterbalance a dramatic increase in care needs.

Declines in the state’s child population reflect low birth rates. Like the rest of the United States and most developed countries in the world, California has experienced a sustained decline in birth rates. In California, the total fertility rate—the average number of births in a woman’s lifetime—has fallen from 2.15 in 2008 (just above the level needed to replace the population) to 1.47 in 2020. The Department of Finance projects that these low levels of fertility will persist into the future.

Declines in the population aged 16 to 64 are driven primarily by interstate out-migration. For several decades, California has experienced substantial net outflows to other states, particularly among less-educated Californians. International immigration to the state counterbalanced some of this population decline, but the flow of immigrants has been modest in recent years.

Growth in the older adult population will vary across counties

While all regions of the state will be impacted by growth in the older adult population, regional differences are a key consideration for planning and policy. The DOF population projections provide information at the county level, which we use to provide a high-level picture of how older adults will be distributed across the state (Figure 2).

Increases in the population of adults 65 and older in the Far North region of the state will be much lower than the statewide average. Several counties near the northern border are projected to see little or no growth—including Shasta, one of the largest counties in the region. Many Bay Area counties—including Alameda, Santa Clara, and Contra Costa—will see growth rates in the 70 to 80 percent range. In contrast, counties in the Central Valley (e.g., Kern, Stanislaus, Fresno, and Kings) are projected to have lower than average growth (about 40%), as are Central Coast counties including Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo. Most large Southern California counties, including Los Angeles, will see increases around the state average (60%); this is not surprising, given that such a large share of the state’s population resides in that region.

When we look at growth among adults aged 85 and older, the regional patterns shift somewhat. Now the Far North region stands out with some of the largest increases; in a few counties—including Mendocino, Trinity, and Plumas—the over-85 population will more than triple by 2040. Most large Bay Area and Southern California counties will see their populations age 85 and older more than double. Although counties such as Fresno and Stanislaus will have lower than average increases in older adults, they will see considerable growth (80%) in this age group.

California’s Older Adult Population Will Be Diverse

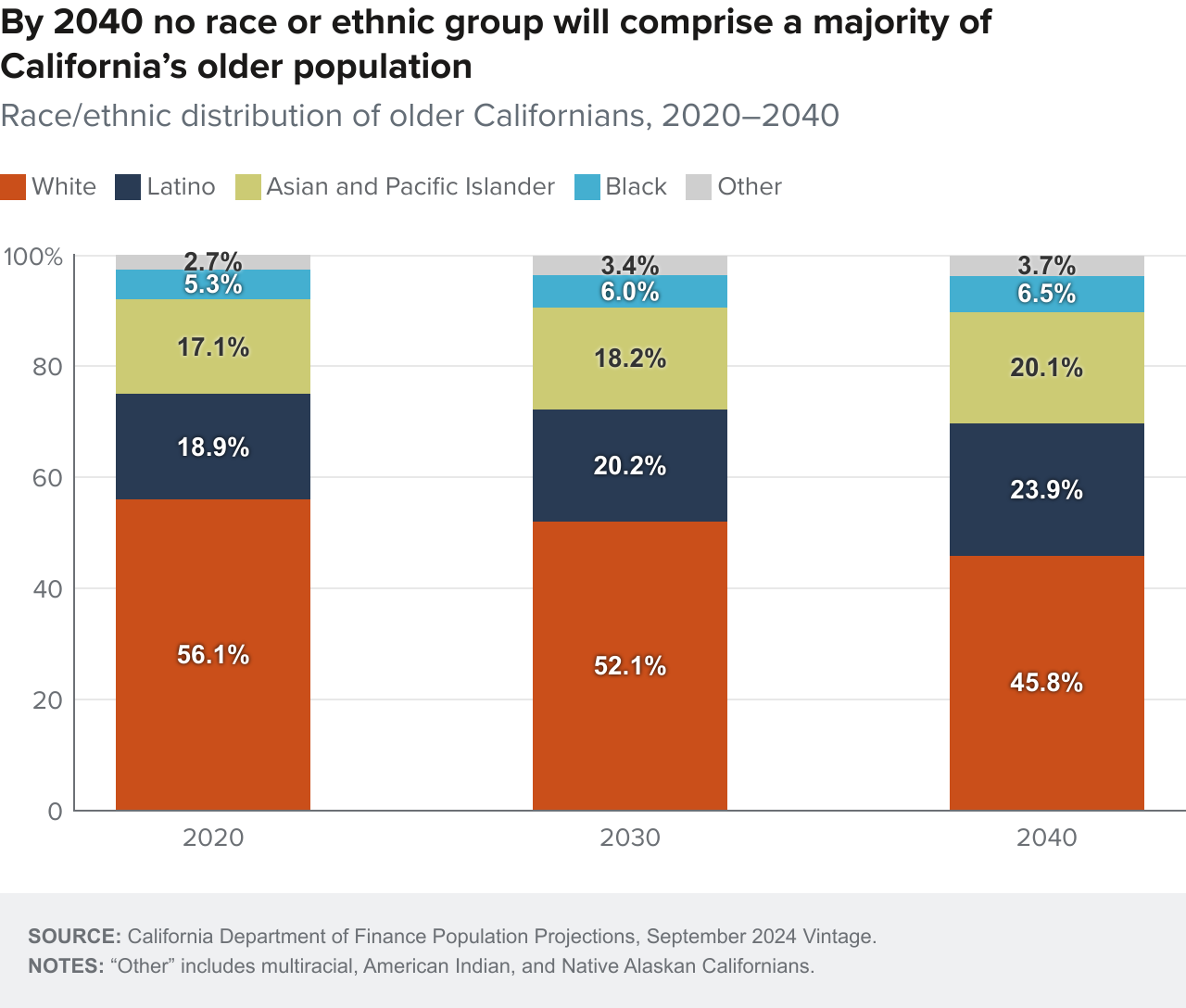

The racial/ethnic composition of California’s older adult population is projected to become increasingly heterogeneous, with no single racial or ethnic group constituting a majority of the older adult population. The number of Latino, Asian, and Black older Californians is expected to double or nearly double by 2040, while the older white population will increase by 30 percent. While whites are projected to remain the largest racial/ethnic group of older adults, their relative share will decrease as other groups grow more rapidly (Figure 3).

A key driver of diversity among older adults is the dramatic increase in immigrants from Latin America and Asia in the 1980s. Upon arrival most were young adults, primarily in their 20s and 30s. Those early large cohorts of immigrant arrivals from the 1980s are now in their 50s and 60s, beginning to fundamentally alter the ethnic composition of California’s older population.

It is worth noting that in recent years, migration of older adults, both international and domestic, has not been a primary driver of the growth and diversity of California’s older population. Instead, the growth in the state’s older population is primarily driven by the aging of existing residents, including those who immigrated decades ago, and their increased life expectancy.

Some counties will see more growth in Latino and Asian older adult populations

There will also be variation across the state in racial and ethnic changes in the population of older adults (Figure 4). In 2020, only 12 counties did not have a majority-white older adult population; by 2040 that number doubles to 24 counties. As previously discussed, the population of adults 65 and older who identify as Latino and Asian and Pacific Islander will more than double by 2040 and the older Black population will nearly double (90% increase). Counties that will see the highest growth rates in Latino older adults include relatively smaller counties like Mendocino and Marin, along with larger counties such as Monterey and Orange. Among Asian older adults, Santa Clara County will have one of the highest increases, with the number of adults aged 65 and older of Asian and Pacific Islander descent growing from about 98,000 to nearly 225,000.

The number of foreign-born older adults will increase significantly

The share of older adults who are foreign born is expected to increase to over 40 percent by 2040 (compared to 29% in 2020), again reflecting immigration patterns from decades ago. The largest increases will be among 65 to-74-year-olds (Figure 5). The majority of Latino older adults (59%) will be foreign born, similar to levels today. Almost 9 of 10 Asian older adults will be foreign born. Again, these levels are similar to those of today.

Consistent with trends in population gains among foreign-born older adults, the share of older adults who speak a language other than English at home is projected to increase from 35 percent to 42 percent. According to 2021 and 2022 American Community Survey data, Spanish is the most common language spoken by older adults who speak a language other than English at home (46.9%), followed by Chinese languages, Mandarin or Cantonese (12.1%), Filipino or Tagalog (10.4%), Vietnamese (5.1%), Korean (3.8%), and Hindi and related languages (3.7%). Latino and Asian older adults will remain especially likely to speak a language other than English at home, although both shares are projected to be slightly smaller (Figure 6).

Older Californians’ Economic Circumstances Vary

Economic security for older adults hinges on a number of factors, including housing stability and financial well-being. As incomes decline, many older adults face a decline in their standard of living and struggle to make ends meet especially given the state’s high cost of living. The PPIC Statewide Survey finds that more than a quarter of adults worry every day or almost every day about having sufficient funds for retirement. Lower-income workers are especially anxious, with 40 percent of those in households with incomes of less than $20,000 per year reporting worrying every day or nearly every day.

Economic conditions among California’s older adults in 2040 will be complex and varied. While many will enjoy the stability of homeownership, a significant portion will face financial challenges that could impact their ability to age in place and maintain a good quality of life. Black and Latino older residents will face even greater challenges, with higher shares projected to be renters with low incomes.

Homeownership Is Key to Housing Stability

By 2040, the vast majority (70%) of older adults are projected to be homeowners, down only slightly from 73 percent in 2020 (Figure 7). Most of these homeowners are likely to have accumulated substantial equity in their homes. This high rate of homeownership provides a degree of housing stability for many older adults, but it doesn’t necessarily translate to overall financial security. Further, many who age in their homes are likely to need modifications; navigating stairs is the most common daily activity that older adults need help with (Maresova et al. 2019). About 35 percent of older California homeowners in 2022 owned their homes outright and may be “housing rich, income poor”—that is, they may have significant home equity but limited liquid assets or income. Another third have mortgages and may struggle to make payments as their incomes decline during retirement.

However, the 30 percent of older adults who are projected to be renters in 2040 are likely to face greater financial challenges. Renters are much more likely to be financially burdened by a combination of low incomes and rising housing costs. This group may face greater challenges in maintaining stable housing as they age. While adults over 65 make up only a small share of Californians experiencing homelessness, this group has experienced the largest growth in homelessness over the past five years (see Technical Appendix C for more details).

Our models suggest that homeownership will rise relatively steeply among older Asian Californians while stagnating or declining among older Californians in other racial/ethnic groups. Renting will continue to be especially common among older Black (45% in 2020 and 43% in 2040) and Latino (34% in 2020 and 37% in 2040) residents.

More Older Adults Will Remain in the Workforce

Labor force participation rates for 65- to 74-year-olds are projected to increase over the next 15 years. The largest gains in participation will be among those aged 65 to 69, driven at least in part by the age at which people are eligible for full social security benefits being raised to 67. This suggests that more older adults may be working out of necessity rather than choice, particularly those with lower levels of education and perhaps lower lifetime earnings. These increases in labor force participation will be mostly offset by increasing shares of adults 75 and over who will not be working (Figure 8).

We see only minimal shifts in labor force participation rates by race/ethnicity (Figure 8). While older white and Black adults had higher rates of labor force participation in 2020, our models suggest a narrowing of the racial/ethnic gap. By 2040, about 18 percent of older adults across all racial/ethnic groups will be in the labor force. This likely reflects the older age structure of white Californians relative to Latinos and Asians.

Substantial Numbers of Older Californians Will Have Low Incomes

The variation in income as people age makes projections challenging. Nonetheless, an assessment of poverty levels is important in understanding economic well-being among older adults, especially as it relates to eligibility for Medi-Cal, California’s Medicaid program, which covers the cost of long-term services and supports. Our model suggests a modest decline in poverty and near-poverty rates among older adults (Figure 9). The share of older adults with incomes less than two times the federal poverty level (about $19,700 for a two-person household in 2023) is expected to decrease from 24 percent in 2020 to 22 percent in 2040. The oldest age groups will remain especially likely to live in low-income households, with about one in four adults aged 80 to 89 living in or near poverty. Overall, the number of older Californians with low incomes is expected to grow from about 1.4 million in 2020 to nearly 2 million in 2040.

Because the population of older adults will be growing, there will be many more low-income older adults across all racial ethnic groups. Our projections suggest that Black and Latino older adults will continue to have higher rates of poverty or near poverty than white and Asian older adults. While we project relatively large declines for Latino older adults and moderate declines for white and Asian older adults, the increasing trend in poverty among older Black adults is cause for concern (Figure 9).

Projected declines in poverty rates among older adults are consistent with supplemental poverty measures, which provide a more holistic accounting of poverty by factoring in items such as housing costs and medical expenses (refer to Technical Appendix A for more details). SPM poverty rose among older adults in 2022; it will be important to monitor this trend.

Living Arrangements and Well-being Are Key Concerns

As California’s population ages, living arrangements and well-being become increasingly important considerations for policymakers and service providers. Recent trends and projections highlight several key issues related to the way older Californians will manage their daily lives in the coming decades.

Older adults overwhelmingly express a desire to stay in their homes and communities as they age—or to “age in place.” Policies such as in-home supportive services aim to support older adults in maintaining their independence and quality of life within familiar surroundings. At the same time, improvements in health have lowered age-specific rates of difficulty with self-care and independent living. In other words, older Californians begin to experience difficulties caring for themselves later in life than they used to. However, the dramatic increases in the 85-plus population over the coming decades will lead to large increases in older Californians who need help.

Family connections will continue to play a crucial role in the living arrangements of older adults. By 2040, the majority of older Californians are projected to be living with family members, with 59 percent residing with a spouse and a significant portion living with other family members. Multigenerational family households are important and growing, and are especially common in older Latino and Asian communities.

The share of older adults living alone is expected to decrease from 22 percent to 19 percent; this shift is partly attributable to increased life expectancy among men, which will mitigate the number of women living alone in their later years. However, gender disparities in longevity will persist, with older women aged 80 and over remaining the most likely to live alone (28%). Owing to a greater prevalence of multigenerational households, Asian and Latino older adults will remain much less likely to live alone than their white or Black peers (Figure 10).

Aging in place will be challenging for many older adults. Key reasons why older adults lose independence include the onset of disabilities; psychological and cognitive problems; mobility challenges; falls, wounds, or injuries; nutritional issues; and communication difficulties (Maresova et al. 2019). Among adults over 80, one in three will have difficulties living independently (i.e., staying in their homes without assistance and caregiving services), while one in five will struggle with basic self-care activities such as dressing and bathing. Even though rates of self-care limitations are projected to decline, the large increase in older adults, especially those age 80-plus, will swamp these improvements in rates. We project that more than 914,000 older adults will have self-care limitations in 2040, compared to 668,000 in 2020. Similarly, we project a sharp increase in the number of older adults with independent living difficulties, from 1.1 million in 2020 to 1.9 million in 2040. Independent living difficulties will rise dramatically among older Black and white adults, largely because higher shares will be age 80 and over (Figure 11).

Despite the prioritization of aging in place, some older adults will need institutional care. The number of older adults in institutional group quarters is projected to increase by 51 percent by 2040, primarily driven by the doubling of the oldest old population (80 and over). Finding appropriate living situations for those needing institutional care will likely require additional capacity in nursing homes, a notable challenge given the lack of new spaces in the recent past. However, even with this increase, only 3 percent of older adults are expected to live in institutions, underscoring the continued preference for home-based living arrangements.

Policy Implications and Next Steps

The substantial growth in the older adult population poses major fiscal and policy challenges for California. The good news is that by some measures—such as living longer and living in their own homes—older Californians in the future will be better off than today’s seniors. However, the rapid increase in the older population—especially the oldest old—means that the number of older adults needing help of some sort will grow dramatically. Our projections show an economic bifurcation of the state’s rapidly growing older population. Those who own their own homes and have adequate savings for retirement will obviously have more resources to take care of their needs as they age, but a large group of older Californians, especially renters, will face numerous challenges including simply affording a place to live.

These demographic projections highlight the need for policymakers, health care providers, and community organizations to prepare for a future where older adults represent a larger and increasingly diverse segment of California’s population. Moreover, the significant growth in the older population, particularly the oldest old, will necessitate careful planning to meet the increased demand for age-related services and support, since older ages are highly correlated with illness and disability (Tesch-Römer and Wahl 2016). The changing composition of the older adult population will require culturally sensitive approaches to service delivery and policy development to ensure that the needs of all groups are adequately addressed. This includes not only addressing language barriers but also understanding and respecting diverse cultural norms and preferences in health care, social services, and community engagement.

Many Californians Are Financially Unprepared to Retire

Studies on retirement readiness reveal significant financial insecurity among California’s aging population, and these trends are projected to continue until 2035 (Ebner and Rhee 2015). Demographic analyses of middle-income older adults in California predict that by 2033, many will face mobility limitations and chronic conditions, and will be unable to afford assisted living without selling their homes (Pearson et al. 2022). Additionally, financial disparities are particularly pronounced among Black and Latino communities within this group (Munevar and Rayel 2024). Sudden changes in health, disability, and marital status can lead to significant financial hardship for older adults, often resulting in Medicaid enrollment (Johnson and Favreault 2021).

The increase in labor force participation among 65- to 74-year-olds, particularly those with less education, may require workplace adaptations and policies to support older workers. The Master Plan for Aging encourages employment and volunteer opportunities for older adults, especially in roles that foster intergenerational engagement. But the economic divide among seniors may necessitate targeted interventions to support those with the greatest financial need while also addressing the unique challenges of the “housing rich, income poor” population.

Older adults with incomes too high to qualify for Medi-Cal face high and rising costs for long-term care in assisted living facilities and nursing homes. In California, a semi-private room in a nursing home cost about $137,000 annually in 2023, an 8 percent increase over the previous year (Genworth 2023). Wealthy individuals may choose to self-insure by saving enough to cover long-term care expenses (Marotta 2022). For low- and middle-income Californians, however, managing the risk of financing this high level of care is a major challenge.

Middle-income older adults who cannot self-insure and do not qualify for Medi-Cal may choose to purchase long-term care insurance. However, premiums can rise, and coverage can be limited (Marotta 2022). In a worst-case scenario, individuals pay premiums for years only to have their insurer go out of business before they can collect on any coverage. Washington state has created a public long-term insurance program; its WA Cares Fund pays for long-term care out of a payroll tax (WA Cares Fund 2024). However, lifetime payments are capped at $36,500, a limitation that highlights the difficulty in truly insuring an entire population against the risk of long-term care.

Workforce and Budget Priorities Will Need to Shift to Address Growing Demand for Health Care

Growth in the aging population is in part due to advances in public health and medicine, but longer life spans involve frailty and disability (Rowe et al. 2016). The state will need to transform several sectors to meet the needs of the fast-growing group of adults 60 and older, along with the more complex needs of those aged 85 and up, a yet-faster-growing group (Department of Aging 2024). California’s Master Plan for Aging identifies priorities and calls on stakeholders in the public, private, and philanthropic sectors to help prepare for this new demographic era. The plan calls for a reimagined approach that includes both health services and healthy communities.

Health services will need to transform to respond to increased and changing health care needs. The growth of geriatric expertise in health care is not on track to meet demand. The Institute of Medicine highlighted the need for a health care workforce to serve an aging population in 2008, but its call to action was followed by a decline in geriatricians and nurse practitioners who work with older adults, and health professions education still does not require classes in geriatrics (National Academy of Sciences 2023). In California, a mere 5 percent of providers have training in geriatrics (Department of Aging 2024). Beyond physicians, nurses, and other well-paid health professions, the state will need to bolster its care workforce with more workers in roles such as home health and personal care aides (McConville, Payares-Montoya, and Bohn 2024). These are some of the fastest growing jobs in the state, but they tend to pay low wages and have high turnover (McConville, Payares-Montoya, and Bohn 2024).

The health needs of older adults will also have a major impact on state spending, as Medi-Cal is the most common payer for long-term services and support in California. Nationally, long-term care costs account for over 30 percent of Medicaid spending (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2020) and are projected to grow along with the aging population (University of Pennsylvania 2022).

Community and Families Will Be Central to Meeting the Care Needs of an Aging Population

Healthy aging used to be considered an alternative to aging with disability, but researchers now recognize that most aging adults experience both healthy and disabled years (Tesch-Römer and Wahl 2016; Kahana et al. 2019). Older adults not only have a greater number of illnesses than younger adults, but they are also more likely to have some of the most difficult-to-manage conditions, including Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and other dementias. At some point, most older Californians will become dependent on others for help with daily activities, with a significant increase in dependency after age 80 (Maresova et al. 2019).

Older adults will need a range of formal and informal services during their more disabled years. The Master Plan for Aging elevates the role of communities. The plan also argues for housing that can support multigenerational families and/or caregivers. The high rate of homeownership among older adults suggests a need for programs that help homeowners maintain and adapt their homes as they age. For renters, affordable housing options and rent support programs may become increasingly important to prevent displacement and homelessness. The substantial share of older adults living in or near poverty indicates a need for robust social support programs and expanded eligibility for existing programs. It also points to the major role Medi-Cal is poised to play as the primary payer of long-term services and supports (LTSS), including nursing home care and home- and community-based services (HCBS).

For those who need help with daily activities such as bathing and dressing, HCBS services are much less costly than the alternative of institutional living, and these services help honor many older adults’ wishes to age in place. The range of services is substantial—from adult day services in community centers to home care services. The In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS)—the largest state program designed to help older adults maintain their independence—plays a critical role (Beck 2015; McConville, Payares-Montoya, and Bohn 2024). Notably, 70 percent of IHSS workers are family members of the care recipient, and half of these workers live with the person being cared for. This high proportion of family caregivers highlights the crucial role that family support plays in enabling older adults to age in place.

A recent policy change that eliminated the asset test for Medi-Cal is especially consequential for middle-income older adults. Previously, a person needing long-term care needed to spend down their assets in order to qualify for long-term care—but could not spend down (for example, by distributing early inheritances to family members) within 30 months of applying for coverage. With the elimination of the asset test, the 30-month rule is being phased out for applicants needing long-term care and eliminated for other groups (Department of Health Care Services 2023). As a result, middle-income Californians who have some assets but low or no income will be more likely to qualify for Medi-Cal.

California’s Medi-Cal program currently spends $22 billion annually on HCBS; as we have seen, demand for these services will increase dramatically, and there is insufficient data to monitor their effectiveness. The state’s California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM) initiative (California Health Care Foundation 2021) aims to enhance oversight of HCBS through Medi-Cal managed care plans (Harrison, Shih, and Ahluwalia 2022; Chapman and Evenson 2023). As HCBS demand rises in California, the state will need to develop policies that enhance geographic provider coverage, improve communication, and simplify access. Initiatives like the Aging and Disability Resource Connection can play an essential role (Kietzman et al. 2022).

CalAIM also includes community supports such as medically tailored meals and transitional care to those moving from a nursing facility to assisted living or back home. Programs such as Meals on Wheels or senior centers can serve those who can no longer prepare their own food at home. We learned from the recent COVID-19 pandemic that isolation and loneliness had detrimental effects on older adults (Kotwal et al. 2021). Senior centers can also provide exercise classes, intellectual stimulation, and social interaction that are crucial for older adults’ mental health.

As California’s older population becomes more diverse, the need for culturally and linguistically appropriate care for older adults will grow. While technological advances such as telehealth are making care more accessible for older adults—particularly those with mobility or transportation challenges—the current systems are not sufficient to serve patients with limited English proficiency (Rodriguez et al. 2021). Another important component of equity involves providing care for the aging LGBTQ+ population; California has the largest LGBTQ+ population in the country (Flores and Conron 2023), and older sexual minorities are more likely to have never married and to live alone compared to older straight adults (Choi, Kittle, and Meyer 2018). Additionally, older adults living with HIV are at risk of some comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease (National Institutes of Health Office of AIDS Research 2024). Like other minority groups, LGBTQ+ older adults will need culturally appropriate health care services.

Next Steps

As the number of older adults increases, particularly those requiring assistance with daily living, the state will need to allocate more resources to programs and services that support this population. To meet the challenge of supporting California’s growing population of older adults, state and local governments are working to implement the Master Plan for Aging. Multiple research, policy, and funding efforts are under way to support this initiative. Our own research has yielded some encouraging findings. Rates of older adults living alone are projected to decline, and most older Californians will own their homes, often with substantial equity. These factors can contribute to stability and well-being in later life.

However, our projections also reveal concerning trends. The economic divide among older Californians is likely to remain large, with substantial numbers of poor or near-poor older adults and a rise in the proportion of renters. Moreover, the demand for services meeting the needs of older Californians will grow dramatically, primarily due to the projected doubling of the population aged 80 and over.

With the aim of helping policymakers and service providers accommodate the state’s changing demographics, PPIC’s Understanding California’s Future initiative plans to build on these initial findings. Key areas of focus may include housing and homelessness, long-term care affordability, and regional variations in aging and services. We may also focus on older adults who may be particularly vulnerable or have unique needs, including labor force participation among those who are poor and near-poor or who have health conditions such as HIV or dementia. By delving deeper into these areas, we hope to provide policymakers and stakeholders with insights that can help them create effective, targeted interventions and programs. As California’s population continues to age and diversify, ongoing research and policy development will play a crucial role in ensuring that all Californians can age with dignity, security, and a good quality of life.

Topics

Economic Trends Economy Health & Safety Net Housing Population Poverty & Inequality